In the spring of 1952, twenty-four-year-old newspaper reporter Roger Kahn, traveling with the Brooklyn Dodgers for the first time, decided to pay Jackie Robinson a surprise visit at the Sir John Hotel in Miami Beach. Kahn was convinced that the integration of baseball was still the most important sports story of the time, and wanted to solicit the all-star second baseman’s thoughts on the state of integration, six years after his historic 1947 breakthrough, for a Sunday feature in the New York Herald Tribune.

Though Robinson had established himself as one of the game’s best players and biggest gate attractions, he and his black teammates were, Kahn was dismayed to learn, still considered second-class citizens in south Florida. While the Dodgers clubhouse had become, by this time, a model for progressive attitudes towards race, black and white ballplayers still had to go separate ways when the games were over. The white players and the sportswriters, all of whom were white, stayed at the posh McAllister Hotel on Biscayne Boulevard, while the black players stayed at the Sir John, in the city’s northern quarter.

Kahn knew that the Sir John was a black hotel but didn’t think much of it until Robinson told him, shortly after they greeted each other, that he was the first white reporter ever to visit there. “You’ve broken a color line,” Robinson said.

What followed was a candid and revealing interview in which Robinson shared his thoughts on a wide range of topics, from integration’s progress to the abuse he had endured from fans and certain members of the media to his feelings on the men who brought him to Brooklyn, Branch Rickey, the former Dodger General Manager since exiled to Pittsburgh, and Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers’ owner. It was a provocative interview, full of lively quotes, and Kahn was so proud of his reporting that he sent the feature, entitled “Jackie Robinson on Integration,” through to his editor in New York, Bob Cooke, via Western Union, night press rate collect.

Jackie Robinson signs his contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers as Branch Rickey looks on.

But as Kahn, now 89, explains in his book, Rickey & Robinson: The True Untold Story of The Integration of Baseball, Cooke was no champion of integration, and the Yale-educated sports editor of the Herald Tribune made little effort to disguise his opinions. Over a drink one night, Cooke told Kahn with great conviction, that by signing Robinson “Rickey has done more to damage baseball than any man who ever lived.” So it was not of great surprise to Kahn that Cooke killed the story. Robinson had predicted as much. “Suddenly,” Kahn writes, “I recognized the crippling limitations imposed on my assignment. Write about the first integrated Major League Baseball team, but be careful. Never, ever mention integration.”

Kahn was disheartened but at twenty-five also reluctant to risk what he later called a “career crisis,” and did not challenge his editor for his bigoted views. Instead, he bided his time, continuing to think critically and report on race, if mostly for his own notebooks. Before long, an exciting new opportunity arose: A sports magazine bold enough to report on issues the mainstream press refused to, edited by Jackie Robinson.

“Our Sports aims to corral all the activities of Negroes in sports into one interpretive medium for the vast Negro audience,” Robinson wrote in the magazine’s May 1953 debut issue. Though many of its editors were white, Our Sports was targeted toward underrepresented blacks and forward-thinking whites and sought to examine the black sports experience through an objective lens. After six years of speaking through writers whose interests didn’t always align with his own, Robinson finally had an opportunity to get his own words and ideas into print consistently, and to control their message. The idea intoxicated him.

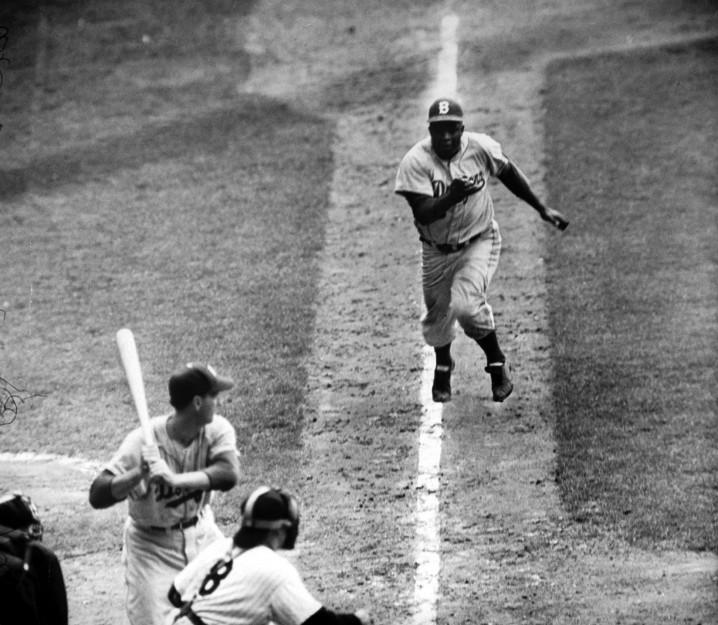

Though he had been moved to the outfield to make room at second base for fleet-footed rookie phenom Jim Gilliam, Robinson was still a vital part of a Dodgers team that won 105 games and the National League pennant in 1953. His hands full with a pennant race, he needed all the help he could get with the magazine. Robinson asked Kahn to assist him with the editing of his monthly column, to contribute his own monthly story and to consult with the magazine’s editors from time to time.

“My enthusiasm matched his,” Kahn writes in Rickey & Robinson. “I was excited to start working closely with a complex, brilliant and heroic man.” Story ideas began pouring out of him as they did Robinson, as each man, from his respective viewpoint, had been turning over issues of race in his mind for some time. Not unlike Robinson as a ballplayer, the magazine’s potential seemed boundless and exciting.

In a series of absorbing articles, Our Sports took such bold stances as proposing pitcher Satchel Paige for enshrinement into the then-all-white Baseball Hall of Fame, openly campaigning for the hiring of a black major league manager, and challenging the unwritten rule that barred blacks from competing as jockeys. For the second issue, Kahn interviewed more than fifty ballplayers, coaches and executives for a feature entitled “What White Big Leaguers Really Think of Negro Players.” Robinson followed that up one month later with “The Branch Rickey They Don’t Write About,” a lengthy admiration of his friend and mentor. “Without Branch Rickey there probably would have been no Jackie Robinson in baseball, nor a Monte Irvin or a Larry Doby,” Robinson wrote. “At a time in life when most men settle down in rocking chairs, Rickey launched a crusade. He battled until the crusade was a universally recognized success. He succeeded because he had something called guts.”

Our Sports was also ahead of its time. Paige waited another seventeen years before his call from the Hall. Twenty-two years passed before Frank Robinson became the Major League’s first black manager, and the relegation of blacks to the position of exercise riders persisted at American racetracks into the 1980s. But to its detriment, the magazine also turned out to be ahead of its time commercially. Unable to attract major advertisers, who underestimated the strength of the black market, the magazine lasted only five issues despite its powerful and pioneering reporting. Few copies remain.

That same year, Robinson telephoned Kahn at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis to inform him that during the previous night’s game Eddie Stanky, his former Dodgers teammate then in his second season managing the Cardinals, held up a pair of shoes when Robinson came to bat and yelled “Hey, boy! Shine these!”

“I’ve been in the league for six years and I don’t think I should have to put up with this shit anymore,” an angry Robinson told Kahn. Stanky denied the allegation but later conceded that in an effort to win a ballgame he would bother Robinson any way he could.

Suspecting it would raise the ire of his editor, Cooke, Kahn wrote and filed the story anyway. Somehow it made its way into the early edition of the next day’s Herald Tribune. When Cooke read the piece, he had it spiked in all subsequent editions of the paper. Shortly thereafter, Kahn received a telegram at the Chase. “We will not be Jackie Robinson’s sounding board,” Cooke wrote tersely. “Write baseball, not race relations.”

While the story was killed, Robinson appreciated the sincerity of Kahn’s effort. As their relationship evolved over the ensuing years and their mutual respect blossomed into trust and, later friendship, Kahn earned a level of access to Robinson—a complex and fascinating individual—that was unparalleled in the mainstream press.

Robinson signing autographs for fans outside of his home.

Still, several of Kahn’s earliest stories on race never made it into print. Our Sports failed both on Madison Avenue and at the newsstand, and Kahn was pulled off the Dodgers beat and reassigned to cover the rival Giants (he left the paper in 1955 citing an inability to accept Cooke’s censorship). These setbacks convinced Kahn that, as he writes, “the field of socially conscious sportswriting was wide open.” Furthermore these experiences informed much of his later work, including notable magazine features for Esquire, Sports Illustrated, Time, The Saturday Evening Post, and, nearly two decades later, his classic bestseller, The Boys of Summer, a landmark work that forever altered the way people wrote about and thought about athletes as people. It created a whole new idea of how sports could and should be covered, its depth and breadth, and inspired thousands of young baseball fans to contribute a verse.

Inspired by Robinson’s courage, grace, and the integrity of his example, Kahn established himself as one of America’s most renowned sportswriters. In The Boys of Summer (1972), the Pulitzer Prize-nominated The Era (1993) and now Rickey & Robinson, he uniquely chronicled and illuminated the turbulent grip of years bookended by Robinson’s career, 1947-1956, with unsurpassed insight. Few writers, including Kahn’s many admirers and imitators, have more eloquently examined sports as a lens through which we view ourselves and, in turn, our times. And as much as sports and sportswriting have changed in the intervening years, Kahn has remained a steadying constant, a writer every bit as dedicated to speaking his conscience as he was the day he first visited Jackie Robinson at Miami’s Sir John Hotel.