With the NBA season having recently wrapped up, the coaching carousel has begun in earnest. Teams that think they're not getting the most out of their talent will be searching for up-and-coming assistants and retread head coaches to lead their squad. And those new head coaches will need to fill out their staffs, while any assistant coaches hired away will need to be replaced by their old teams.

No other time of the year sees as many NBA jobs opened up and filled. But with all these opportunities, second-chances and first starts being handed out, there's almost no doubt that a coach who has spent the last several years dominating the CBA and Canadian National Basketball League won't be given a chance to sit on an NBA bench next fall.

That's surprising, since that man is Micheal Ray Richardson. Or, it's because it's Micheal Ray Richardson.

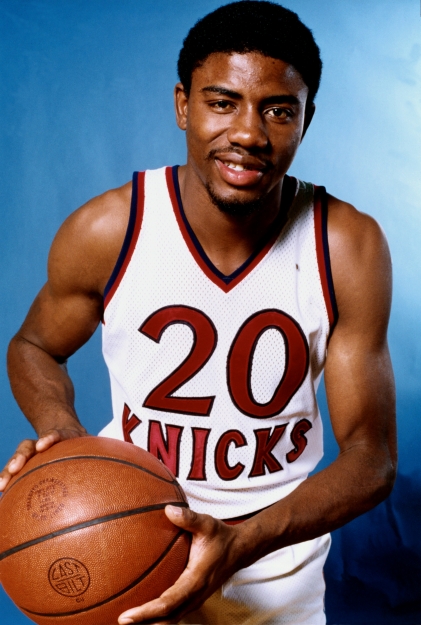

The lanky combo guard, four-time All-Star and two-time All-NBA Defensive Team selection that electrified crowds in New York and New Jersey (with a year in Golden State thrown in) during the late 1970's and early 1980's has surprisingly remade himself as a minor league basketball coach after being banned from the NBA in 1986 for violating the league's drug policy. Now, Richardson's path to return to the league is clear, but his opportunity lags behind.

“If there was one player in the history of sports that his past has haunted him,” Richardson's former New Jersey Nets backcourt-mate Otis Birdsong said, “It would be Micheal Ray. I don't think people have forgiven him. If they have, they certainly haven't forgotten him because you don't have as much success at the minor league level as he's had and not get a shot.”

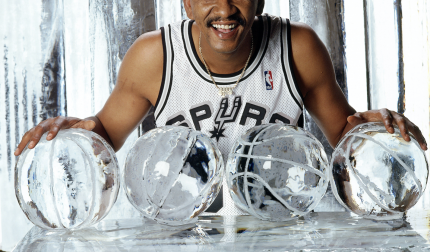

Richardson's success as a coach is not something that needs to be explained with player anecdotes or video breakdowns of his schemes, he's won too many titles for that to be necessary.

Since getting a call at the end of 2004 from Jim Coyne and being offered the chance to coach the Albany Patroons—the CBA stop in his post-NBA career—Richardson has a championship ring for every finger. He has two CBA championships from coaching the Lawton-Fort Sill Calvary in 2008 and 2009, a 2010 Premier Basketball League championship after the Calvary migrated to the league, and has taken home the title with the London Lightning each of the past two years since he joined the NBL in Canada. The last year that went by without Micheal Ray Richardson walking the sidelines of a league finals was 2006.

“From Day One, I tell the guys, 'You're here to do one thing—to win a championship,'” Richardson said, “'If you're here for your personal reasons, then you shouldn't be here.' And I'm real honest with them.”

Micheal Ray Richardson's second life as a hard-working minor league basketball coach isn't just shocking to those who haven't had many thoughts about him since he left the NBA spotlight. Even Birdsong, his friend for over 30 years and someone who would later himself employ Richardson when he was the GM at Lawton-Fort Sill, couldn't control his reaction to the news of his old teammate's career-switch.

“I just started laughing because I couldn't believe it. Even though I knew he was smart and he knew basketball and everything and he was tenacious, he was the last person I thought would ever become a coach.”

The strange nature of his journey is not lost on Richardson, but as he would surely tell anyone who asked: any good point guard has the requisite knowledge to coach. It's just a matter of getting players to buy-in.

“It's not about the X's and O's,” Richardson said, “It's about getting the guys to believe in you, to respect you and to trust you and work hard for you. If you get those four things, you're going to be successful.”

While off-the court issues during Richardson's NBA playing career acts as a roadblock to his ability to return to the league, it's a Godsend in the minor leagues. With every player harboring NBA dreams, they look to Richardson – under whom Jamario Moon made the jump from the CBA to the NBA Developmental League before five seasons in the NBA – for the secrets to breaking in.

For his part, Richardson tries his best to dispel their illusions. “What I try to do is explain to them, 'Maybe a lot of times (the NBA’s) not in your cards, but maybe you can go overseas and get $15,000-20,000 per month.'”

At first glance, it would seem pretty difficult to get noticed playing for Richardson. He views point guard play and post defense as the essentials for success, with everything else being secondary. He shuns the idea of star scorers, preferring a balanced attack where no single player is the focal point of his offense. Last season in London, Richardson's top scorer only averaged 14.8 points per game. His ninth-best scorer averaged 10.3.

“If you're looking to get in the NBA by scoring a lot of points, you're not getting there.” Richardson said, “They've got million-dollar scorers. If you're going to get to the NBA you've got to do something that a lot of guys don't do and that's play defense and rebound.”

It's not all about self-sacrifice when playing for Richardson. Backed by an enthusiastic and deep-pocketed owner in Vito Frijia, Richardson has campaigned for NBA-level amenities for his players. His practices are fierce and disciplined, but rarely long. He prides himself on his ability to communicate, and only asks his players to match his level of investment. Admittedly, that's a pretty tall order.

For Richardson, part of reaching an understanding with his players is making it clear that he's, in his words, “a different person” on the court. The flames of the legendary fire that made him a polarizing figure as a player are seemingly diminished when the 58 year-old is engaged in polite conversation, but they rise anew when wins and rings are at stake.

“It's scary,” Birdsong said, “I used to try to calm him down because every play it's as if it's the end of the world. He's on the officials, he's on the players; he really wants to win.” It hasn't all been a controlled burn, either.

A suspension for yelling a slur at a heckler led to the end of his time in Albany in 2007. A clash with referees during the 2011 PBL Finals prompted another suspension and eventually another move to another league, but this time Richardson had plenty of public support. Outrage over one-sided officiating that benefitted the team ran by the league's CEO was so rampant that over half the teams in PBL joined Richardson in his voyage to Canada.

Richardson's transition to life up North has been undeniably smooth and his success has continued, but despite his calls and proliferation of his resume, all signs point to him staying put. While his friends try to caution Richardson that this could be where he remains for the foreseeable future, he points to counterexamples.

Phil Jackson and George Karl aren't just Richardson's proof that the minor leagues have produced great coaches but also that age is nothing but a number when it comes in judging his ability to do the job. And 40-year-old Jason Kidd snatching up a head coaching job fresh off his playing career doesn't discourage Richardson either. The way he sees it, the more teams respect the knowledge of point guards, the better his chances.

The obstacles to Richardson's return don't lie in the Commissioner's Office, either. David Stern, the same man who banned him from the league in 1986, is now counted as a close friend by Richardson and was crucial in landing him a job as a Community Ambassador for the Denver Nuggets prior to his coaching career. “He's one of kind,” Richardson said. “He's a genuine guy.”

And yet, Birdsong, despite being Richardson's friend and one of his biggest advocates, can understand why the opportunity hasn't come for him yet. “It's who you know. You have to get a coach who likes you, knows about you and is willing to take a chance on you,” Birdsong said, “And I'm not kicking against that because I was the same way when I was a GM.”

Until that opportunity comes along, all Richardson can do is try to continue to build goodwill. In the middle of June, Richardson and Birdsong, along with Danny Manning, John “Hot Rod” Williams and others, went down to Moore, Oklahoma to host a free youth basketball clinic and present a $5,000 check for elementary schools and students damaged by the vicious EF5 tornado that ravaged the town in May. “These kids, they went to bed and when they woke up they didn't have anything,” Richardson said.

Both admitted that they had never seen devastation like what lay before them in Moore, but these type of clinics held all over the country have become a regular practice for Richardson and Birdsong throughout the past few years. If Richardson is going to continue to have to wait for his NBA opportunity, it's not a bad way to pass the time.