To this day, Ann Meyers Drysdale remains the only woman ever to sign a guaranteed NBA contract. As an Olympian, Hall of Fame player and broadcaster, she continues to be one of basketball’s greatest pioneers.

We take the US Women’s dominance in Olympic basketball for granted, but you were on the very first US Olympic women’s basketball team in 1976.

When I was in the fourth grade, it was my dream to be an Olympic athlete. At that time, I was very involved in track and field. I was a pentathlete and a high jumper. I had read a book on Babe Didrikson, so that was my dream to represent my country. As I got older, I was very into basketball. I had an older sister and brother who played. I had a dad who played. Basketball opened up a lot of doors for me. Title IX was happening. But it wasn’t until the early seventies that we even knew that there would be a US women’s basketball team in the Olympics.

Why was that?

They had the Pan Am Games and the World Championships, but not the Olympics. Then the ABAUSA, which is now USA Basketball, said that the Olympic Games were contemplating having six women’s teams play. The Soviet team had been together for 12 years. They were essentially pros. And some of the Eastern Bloc countries had teams as well. So when we found out, I started playing for USA Basketball.

So how did the team qualify?

They had four tryouts for the women’s team throughout the country and anyone could try out. You could come and try out (laughs). They had over 300 people trying out at each of these sites. Once they named the final team, the most time we had together was maybe two weeks before the Olympics. We had to go qualify in Hamilton, Ontario. Four teams had already qualified, so they had a pre-Olympic tryout to qualify the next two teams. We won that by beating Bulgaria, and then we headed right to Montreal, but we were told not to unpack because there was a chance that we might boycott the Games. All 12 of us were in one apartment. Eight of us were in two bedrooms, with two bunk beds in each. The rest stayed in the kitchen and living room.

You won the silver medal. What was your plan when you got back to UCLA?

I was the first woman to get a full athletic scholarship at UCLA. I had five brothers and five sisters. My older brother, Dave, played at UCLA and was in the NBA, but education was important in our family. I knew I was going to get my degree. My senior year, we won the NCAA Championship. When I was a freshman, there was talk of a new woman’s league called the Woman’s Professional Basketball League, or the WBL. I was the first pick of the draft, and I decided not to go into the league, because I wanted to play in the 1980 Olympics. So I kept playing USA Basketball, and I became the captain of the team. I was also going after my degree, which was taking a little longer, because I wasn’t in school all the time during the summer, because I was playing USA Basketball. It gave me a chance to try out for the UCLA track team and tennis team. I also played three years of volleyball at UCLA.

As a senior, Meyers led UCLA to the NCAA championship.

For the record, being on the UCLA track team is not like making your high school team. It is the breeding ground of Olympic athletes and world record holders.

Yes (laughs). I loved track and field. Growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, there weren’t many organized opportunities for women in sports other than track and field and swimming. So I was going to get my degree, and after that, I didn’t have a clue, but I wanted to go to the Olympics again. In 1979, Sam Nassi, the new owner of the Indiana Pacers called and said, “How would you like to try out for the NBA?” He knew who I was, and there was no question he was trying to draw some publicity for his team. It was a very difficult decision, but I made the decision before Jimmy Carter boycotted the Olympics. A contract with the Pacers was an opportunity of a lifetime that most men don’t get. I bypassed the WBL, bypassed the Olympics, and tried out for the Pacers. It didn’t work out the way I wanted it to, but it led me into broadcasting. I met my husband Don Drysdale [the Hall of Fame pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers], and it opened up so many experiences.

You knew a lot of NBA players at that point. How did they feel about what you were trying to do?

The biggest thing that I got was that it was fine playing in pickup games at Pauley Pavilion, whether it was with Wilt Chamberlain or Marques Johnson or Mark Eaton. Now this was the real thing. One of the big comments was, “Well you’re taking a job from some guy.” And I’m like, “Well I have bills to pay! (laughs)” Somebody is giving me a chance to make a living. So there were a lot of naysayers, but if you don’t try, you’ll never know. Even if you fail, that’s success. My brother David played for the Milwaukee Bucks, and he was wary, but he was supportive. I trained eight hours a day to get to a different level. It was the best emotionally, mentally and physically prepared I ever was to play the game of basketball.

Your brother, Marc, negotiated a three-year guaranteed contract with the Pacers, which was astonishing for any player at that time.

It was more money than the WBL. The WBL salaries were $7,500-$15,000. We ended up doing a one-year deal with the Pacers for $50,000, and it was a personal services contract. Even though my brother Marc had negotiated a three-year deal, I just wanted one year. And even though I didn’t make the team, I was going to be a broadcaster. I was going to work in the public relations department and learn that end of the business. I was 24 years old. I worked with a lot of wonderful people, and they were apprehensive. “What is our new owner doing embarrassing our ball club with this woman coming in?” But I never felt that I was going to embarrass them or myself or my family. But after two and a half months, I was getting itchy to play. So I left the Pacers. I have made some bad business decisions (laughs). Because it was a personal services contract, once I left, I didn’t get the rest of the money. I signed a three-year deal with the WBL. After the league didn’t pay me all of my money for the first year, I sat out the second year, which is the year the league folded, so I didn’t get my money there either (laughs). My first year, I was drafted by Los Angeles and got traded to New Jersey, where I was co-MVP of the league.

When you decided to tryout for the Pacers, the WBL…

They were not happy with me (laughs)

When you went to the WBL, what was the atmosphere like, given the national attention you had received?

It was a challenge. I definitely had a chip on my shoulder. You have the commissioner of the league saying, “The game has passed her by. There are players better than her.” The one thing I learned from Coach Wooden is that it’s a team sport. You can’t do it by yourself. I had a wonderful coach, but it was difficult, because I was a west coast kid going across the country. They had scheduled a press conference without my knowledge, and I was still on the west coast, fulfilling some of my obligations with the Pacers. When the press conference happened, I wasn’t able to get there on time. It made me look bad. It made the team look bad. It just didn’t start off as a great relationship. I was homesick.

Did you have any other opportunities?

Women’s athletics were just changing. If you look today at the WNBA and all of these women going overseas to play… I had the opportunity to go overseas, which would have made me the first woman to go abroad. But they weren’t paying the money at that time. It’s more difficult for a woman to go in that situation. A guy goes over there and doesn’t speak the language, and women are still picking them up, and they’ve got other guys already living over there. It’s a different lifestyle. For a young woman to go to Italy or Spain or Poland, to not get paid and to be disrespected, it wasn’t a good situation.

What did you do?

I finished out that year with the New Jersey Gems, but it was difficult. Players in the league, it was a challenge for them, you know? “Let’s see how good you are.” So I would get undercut, and I would get hit quite a bit. But hey, I had played against guys my whole life. It was new for everybody. Even the officials. You had all male officials, and they didn’t know how to officiate women at that time at that level. We played the NBA rules. We introduced the small ball, which I didn’t like. I had grown up with a regular sized NBA basketball, so it was an adjustment that I didn’t like. But I truly believe that the WBL is the precursor to where the WNBA is today.

Is it true that you would travel to games to find out that they were cancelled?

Yes. It was insane. There was a game in Houston, where they told us that we couldn’t shower after the game. We had to leave in our uniforms and sweats and hightail it out of there to catch a flight back to New Jersey. There were times where we would get to a game and find out it was cancelled because the team didn’t have the money. And then teams started dropping out. It was a 12-team league. I think it ended up with six or eight teams, before it folded.

So now you’re one of the best basketball players in the world without a place to play?

Things just kind of fell into place. I started broadcasting. I had taken some broadcasting classes at UCLA. In the interim, after my tryout with the Pacers, I had been asked by ABC to try out for the women’s version of the Superstars. It was a TV show where athletes from different sports would compete over two days in these seven events in the Bahamas. And that’s where I met my husband. I didn’t know it was going to be that, but it was. I finished fourth in that Superstars competition. When the WBL folded, I had been sitting out because they hadn’t paid me all my money. So instead, I trained for the Superstars and won the next three Superstars, and was the only woman invited to compete in the men’s Superstars. But during that time, I was hustling for broadcasting jobs. I got a job at KBMG, which did the men’s University of Hawaii basketball games. Remember ESPN didn’t even exist until around the time of my tryout with the Pacers in 1979. The sports world was changing too, so there were more opportunities there.

You had some thoughts about pro golf. Were they serious?

They were, but I had just met Don. The broadcasting was starting to take off too. I got down to a six handicap in about two weeks, because I had this wonderful teacher, and I was totally focused. But I lived a life on the road with basketball, even though it was a team sport. And I know being on the road could be a lonely life. So I think that I was past that. It was challenging to have that kind of opportunity. I played in some of the Pro-Ams in the LPGA, and there’s no question that I could hit the ball as far as they could. But if you haven’t been on the tour in a long time, you’ve got to have nerves, because you’re not going to win all the time. And I’m not good at not winning. For me, it was enticing, but reality-wise, I had to work. I didn’t know if golf would earn me that money. You have to get sponsors and you have to win. And by that time, I had fallen in love.

Anybody I’ve ever met who knew Don Drysdale talks about what an amazing person he was.

Don was great. When he came into my life, the timing was right. He was a competitor. The great line in his era was that if you threw at one of his teammates, he was going to throw at two of yours. And he’d take you down. He had that mentality, and it’s what made him a winner. But he was such a gentleman. He had such a great sense of humor. He was always the guy that brought everybody closer together. When you’d sit and watch him talk with ballplayers he’d played with, he was just as at ease with them as he was with kings and queens, actors and politicians, or the bellman who carried your bags. People would come up to him and say, “I’m still mad at you! The Dodgers left Brooklyn!” He’d smile and talk to them. He always took time to talk to people. He was a common guy, and he never lost that sense of who he was.

Don Drysdale and Ann Meyers Drysdale, hall of famers in their respective sports, were even more competitive on the golf course.

When he died far too young, your children were still very small.

I’ve turned down a lot of jobs. I’m sure the kids would have wanted me there more. Faith, family and friends gets you through a lot of things. My family and Don’s side of the family were always there to help me with the kids. They had to grow up without a father, and they had to grow up with a father that people talked about. And maybe that made him bigger than life and they didn’t know how to live up to him or how to adjust to what people said, because they didn’t know him. That’s been difficult for them. But they are three great kids, and I know that Don would be very proud of them.

How did you arrive at your current positions as vice president and broadcaster for the Phoenix Suns and Phoenix Mercury?

The broadcasting was always there. Early on, after Don’s death, I turned down a lot of things. I did the men’s NCAA tournament for CBS. Then when the WNBA started, ESPN wanted me. But NBC stepped in for six years, and I started doing the Olympics for them. I was doing the WNBA for NBC, which was a one-game-a-week gig that worked out perfectly. Then ESPN brought me back in after my contract was done. It wasn’t a 50-60 game thing, it was more like 25-30 games, which I still thought was a lot because it was taking me away from the kids. Every year since the WNBA came into existence, people were asking me to come to their team to be a coach or general manager or both. In 2007, I felt maybe the timing was right. My oldest son had graduated from high school. My other two kids were in high school. I had a sister living in Phoenix. Maybe I can go back and forth and still be there for the kids. I went to the Phoenix Mercury as the general manager, and we won two WNBA championships in five years. Then they asked me to do more broadcasting for both teams, so that’s what I’m doing now, I’m a vice president for both teams and doing broadcasting for both the Suns and the Mercury.

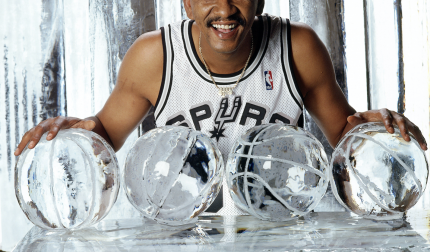

Meyers helped bring championship success to the Phoenix Mercury of the WNBA.

Could you ever see another female athlete receiving an opportunity like you did with the Indiana Pacers? There hasn’t been one since you did it in 1979.

You never know. We do have the WNBA now. To me the one person who could have done it is Diana Taurasi. It has to be a guard. If a woman is 6-foot-4 and a center in our game, she’s not going to be that in the men’s game. So you have to be a guard that can handle the ball. Candace Parker gives you that, or maybe Maya Moore or Elena Della Donne. The playing isn’t the problem to me, it’s the other variables. When I was trying out for the Pacers, there were 11 players on a team, not 15. And you didn’t have the D-League. So you have all these other opportunities to play. On the NBA side, if I sign a minimum contract, it would be something like $475,000. And as the 12th player, you’re not going to play. If you go through the 30 teams in the NBA and take the 12th player, how many minutes are they going to get? It might add up to 15 minutes total per season.

What other challenges would there be?

The biggest thing would be being in the locker room. They would always ask me, “Where are you going to shower?” Well, Wilt Chamberlain never showered in the locker room. He would shower back at the hotel. Plenty of male coaches coach young women in colleges and high school. So what’s the difference? If you have some common decency, you work it out. It’s not just the shower; it’s being on the road with the team. It’s sharing a room. So after a game, when you go out to dinner with teammates, what are the wives going to say? What are the girlfriends going to say? What are the newspapers going to say? What do the other guys say, not only for your team, but from other teams? It’s far more mentally and emotionally difficult than the physical aspect of the game.

We see Becky Hammon and Nancy Lieberman as NBA assistant coaches in today’s game. Do you feel like change has been slow there as well?

It’s slow, no question. Becky was in San Antonio. She knows Gregg Popovich, the head coach. If Pop’s not there, and it’s a younger coach, they don’t take the chance. I’m very proud of Becky and Nancy. Nancy has been in this for the long haul. She was a head coach in the D-league. So how is she not even a number one assistant, with her understanding of the game? You look at sports today, and it’s still dominated by white men making the decisions. There have only been a few women in coaching positions. Rick Pitino did it in Kentucky. But they’ve done polls where colleges have said there’s no way they would hire a female coach. “We’re not ready for it,” they say. Well if you’re not ready for it now, when will you ever be ready for it? You’re never going to be ready unless you do it. So I applaud Sam Nassi for taking a chance on me. I applaud Pop; I applaud Sacramento. It all about taking a chance, whether it’s race, gender or even age. It’s always about relationships.