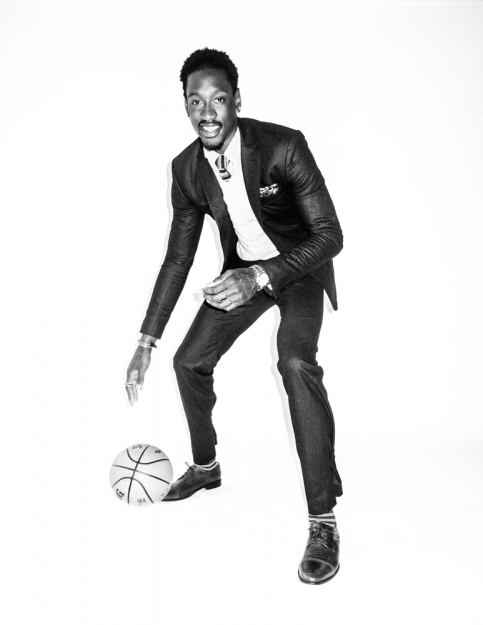

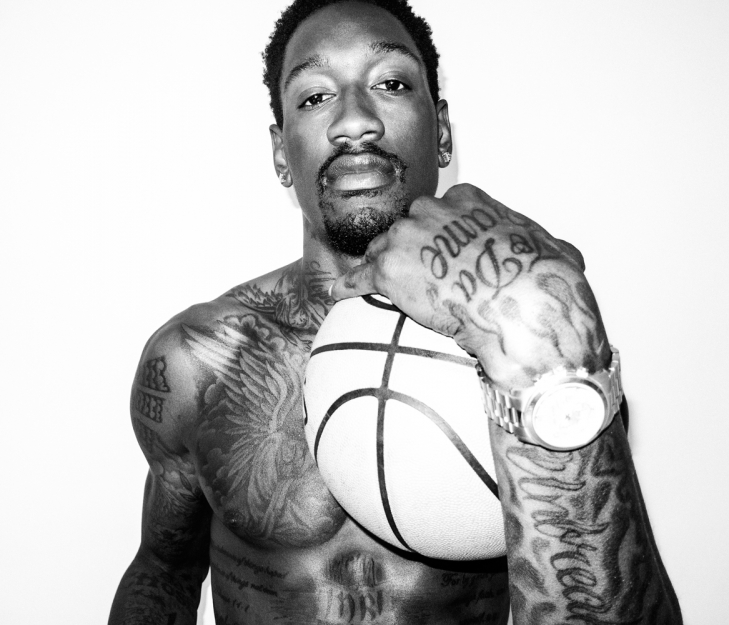

When Larry Sanders is on the road, he likes to write. As the center for the Milwaukee Bucks, he has made himself into a force to be reckoned with near NBA rims. His athleticism and ferocity allow him to challenge any shot, making him one of the league’s premier shot blockers. Off the court, he serenely taps away at his keyboard, creating a novel that reflects a world of his creation.

“The gist of the story is that Earth is a testing ground,” Sanders says. “From there, we either get sent to heaven or out into space, or what we would call hell. If you do something wrong, you get sent to Earth for so many years. You have that time period to overcome whatever obstacles you had in heaven.” The book also includes a bloodline of angels sent to Earth for a spiritual war, an angel in love with a woman in space who tries to rescue her and a look at people trying to escape the repetitive consequences of the things they’ve done wrong. If it has been said that life imitates art, in Sanders’ world, art imitates life.

Whenever Sanders walked around his neighborhood in Fort Pierce, FL as a child, people would stop to talk to him. They all knew his father, Mr. Larry, or Mailman Larry, the six-foot-seven letter carrier with the baritone voice who would wear a suit just to go to the corner store. “Are you the mailman’s kid?” When Sanders would reply that he was, people would often tell him stories about his father. “Some of them were good and some were bad,” he says. “Your dad did this, or he did that. He had his good and his bad. We all do. I had to accept him for what he was. He was my father.”

“My dad is a colorful person,” Sanders says. “He would always speak to people. He really inspired me to be myself no matter what. I didn’t have to conform. He’s 68 now. He once had acid poured over him. It was an episode of domestic violence. He only has one ear because of it. But he’s still so charming and charismatic. He’s still able to portray what is on the inside despite what he looks like on the outside.”

At an early age, Sanders mother moved him and his sister out away from his father. At times they lived in shelters. And while many kids with Sanders’ height dreamed of playing in the NBA, Sanders dreamed of escaping into the world of cartoons. “Growing up, I loved art,” he says. “I would draw anything out of the comics in the Sunday papers. Goofy was my guy. My two-year-old son watches Mickey Mouse clubhouse now, and Goofy is his guy, too.”

Art was a way for Sanders to escape the difficulties his family was going through. Movies were an especially welcome diversion. “I’ve loved film ever since I was a kid. I love the music in movies. I love the way it changes your mood to a particular scene. We didn’t have cable growing up. When my mom would get paid on Fridays, we would go down to the pawnshop and pick out VHS tapes. We’d get things like Jean Claude Van Damme films or Wesley Snipes films and watch them over and over.”

By the time Sanders got to the 10th grade, he was 6-foot-6 and had never played a single game of competitive basketball before. When word got around Port St. Lucie high school that a very tall new student was attending classes, coach Kareem Rodriguez went to investigate. ”They asked me if I had played before and I told them I hadn’t. Coach told me he wanted to teach me. I began to learn that you get out of basketball what you put into it.”

Before entering his senior year of high school, the NBA wasn’t even a dream. “I remember talking to my best friend. I told him, ‘I hope the community college coach comes to the game, so I can get a scholarship and go to college. I played one year of AAU ball. I didn’t know anything about the world of travel ball. That was the first time I had even left the country. That’s when coaches and colleges started to call. It was mostly interest from mid-major schools. Notre Dame was probably the only major school that called. I think they called me and asked me how my GPA was and then they never called back. (laughs)”

Sanders decided to go to VCU, not because they were a basketball school on the rise, but because they had one of the better art programs in the country. “I never did get into the art program,” he says. “It was too demanding.”

He decided to take up sociology instead, something that still interests him deeply. “When I’m finished playing basketball, I want to study different cultures, different social norms. I’d like to apply that knowledge to help businesses reach different parts of societies.”

At VCU, scouts came to take a closer look at a talented guard named Eric Maynor, now a member of the Washington Wizards. But the more they saw VCU play, the more they noticed Sanders. He built enough of a profile for the Milwaukee Bucks to draft him with the 15th overall pick in the 2010 NBA Draft. After an ordinary rookie year, Sanders took a giant leap backward in his second season. People thought he might be a year away from being out of the league altogether.

“I wasn’t prepared my second year. I can see that now. I hadn’t learned what was necessary to be a professional. In the pros, no one is tugging on you to make you do things. You have to develop that work ethic for yourself. You’re the only one expected to push yourself on this level. Going into that second summer, I didn’t have those habits down pat. It was the summer of the lockout. I didn’t have a lot of money. I thought about playing overseas. No one knew when we were going to start. I thought I was in great shape, but my body wasn’t ready for the impact of the NBA.”

Like his novel, needed to learn from the obstacles in his life to reach heaven again. “I had to stumble,” he says. “When I took some steps back in sparked something underneath me. It let me understand that I didn’t have everything figured out.”

This past season, Sanders played with a renewed focus and passion. In Boston, he posted a 20-rebound game. Against the Minnesota Timberwolves, he scored a triple-double, including 10 blocked shots. At the MIT Analytics conference, one presenter made the case that Sanders was the best interior defender in the NBA, forcing players that would ordinarily make over 60% of their shots near the rim to shoot at a percentage below 40%, the biggest difference of any player in the league.

Sanders believes he’s only demonstrated flashes of his ability. “I know I’m not the best player I could be. I want to get better. If I was the best I could be now, I can only get worse from here.”

Larry Sanders may not be satisfied, but he is certainly happy. Happy to have the opportunity to play among the world’s most elite basketball players. He’s happy to have made a new life for his family. And when practice is done for the day, he’s happy to go back to being an artist again.