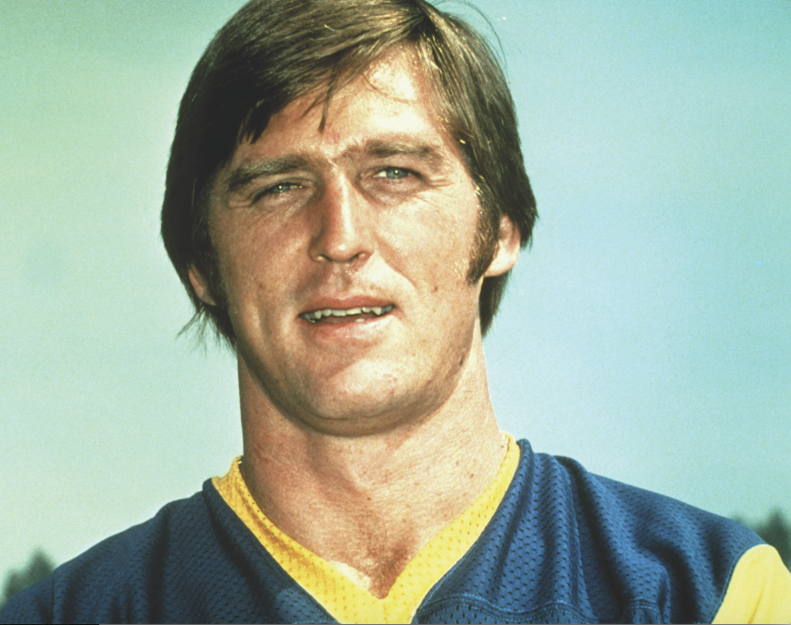

You were a Hall of Famer and an eight-time All-Pro for the Los Angeles Rams. You still hold the record for 184 consecutive starts at strong-side defensive end. How do you feel today?

Just getting older, brother (laughs). I am extremely blessed. I stay in touch with a lot of my guys, and they have far more issues than I do. I like to say that it’s not the model; it’s the mileage. The first thing we do whenever we gather up, everyone shares their stories on what they had fixed and what they’ve had replaced. It’s amazing when you look back on what we did when we were playing the game, as much as we loved it, we had no concept about what we were doing to ourselves physically.

We worry about some of those former players who are alone and struggling out there with their health after their career ends.

You’ve got to remember who we are. We’re athletes. We’re mentally and physically trained to do something. With that, a lot of us have a personal pride that’s hard to overcome and to say, “I need some help here,” because we’re so independent in the way we played the game. I had a hard time admitting that I had some issues with concussions. Four or five years ago, I wasn’t putting two and two together. I explained my issues as though it was because I was sixty-something years old. And when you’re sixty-something, things slow down. From a memory standpoint, it’s all there. It’s just slow to download (laughs). We never thought there was a correlation between bumping your head 27 times a day and your age, and what those bumps years ago caused.

Were you ever diagnosed with concussion or was it just passed off as a “ding?”

Every ding you have is a concussion, and they stay there, and they layer there. In my era, that was expected. It was part of the game. If you don’t get a ding during a game, you’re not playing very hard. You’re not running very fast. You’re not making contact very much. It was the same as being tired, or not being strong enough. It was part of the deal. We knew that they were concussions, but we didn’t have the information for what that meant. To us, it was as much a part of the game as getting your uniform dirty.

Was pro football always the dream?

There was never a dream of pro football, ever. Pro football wasn’t that big in northern Florida. I’m from Monticello, in the Panhandle. Back in the Sixties, we got three television channels, and maybe we saw the Washington Redskins and the Atlanta Falcons. I thought they were the only two teams in the league! I loved to play the game because I was good at it. My high school coach made me believe and taught me how to be good. I realized then that success is gratifying, and it comes with every snap.

So were you at least thinking about a college football scholarship?

I think I got two letters. I was in a high school that had 200 boys from grades 9-12. Monticello was a real small school in Class B. It was divine intervention that the baseball coach for the University of Florida was send to the Panhandle during the playoffs in 1966, and he had one scholarship in his pocket to give to a kid to come and play. I was that kid. There may have been a few Gator fans in town, business guys that were contributors to the University of Florida. I think they went and contacted the coach, Ray Graves and asked them to come look at the tall, skinny kid that was playing middle linebacker.

So was it sheer luck that you got recruited?

Look at it this way. I was 28 miles from the practice field at Florida State, and no one came over to recruit me. Bill Parcells was an assistant coach at Florida then, and he came and looked at us. He went back and told Coach Peterson at Florida, “There’s three or four little players in that school in Monticello that will go on and play.” And that was true, there were about four of us that went on to play at the next level, but Parcells never mentioned me in the report. Coach Peterson said, “What about that tall, skinny kid at middle linebacker?” And Parcells said, “Coach, he’ll never play college football.” I reminded Bill of that at our private lunch in Canton, when Bill was being inducted into the Hall of Fame a few years ago. And as I’m telling the story, Bill leans over to the guy sitting next to him, laughs and says, “That’s a true story!”

If you had no plans to play pro football, what did you think you would do?

I had already taken a job before school ended. I was going to go sit on the floor of a bank. I already interviewed and had made arrangements to move to Atlanta. I had no idea that I was going to be drafted. Not only drafted, but in the first round? No way. There wasn’t the hoopla that goes on with the draft today. My defensive line coach came to me a week or two before and said that there had been some scouts that watched me practice. He said he had an idea that I might be a 10th, 11th, 12th round pick. There were 17 rounds at the time. I thought that would be nice recognition, but I’ve got to prepare for my future.

Was it culture shock to go to Los Angeles?

It was country come to town! I’m not exaggerating. In college, we played in Florida, literally. We didn’t go across the country to play! Up to that point, the furthest west I had ever been was Jackson, Mississippi. I knew where LA was, and I did a little homework on what was going on there, but it was definitely a lifestyle change.

What about the transition to the pro life?

I didn’t understand that I could play at that level yet. They’re saying that I’m a first-round draft choice, so I thought that must mean something. That first year, playing under the tutelage of Merlin Olsen and Deacon Jones, two of the best to ever put on a jock, I began to realize that I could play at that level. It was a little difficult at first, because of the head coach, Tommy Prothro. He drafted me, and he hated me! He told the entire team one night at supper that I was the worst football player that he had ever seen! I made some mistake, and I didn’t do something the way he wanted me to do it. I’m sitting next to Merlin Olsen and Jack Snow, two All-Pro players; they were eight or nine years into the league. Merlin leaned over and whispered, “Don’t worry about it kid. He doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about.” (laughs). But it was shocking for a 21-year-old to hear that from his head coach in front of the entire team.

In 1973, things came together. You became an All-Pro and the Rams won the first of seven consecutive Western Division titles. What came together for you?

Part of it was Chuck Knox, the boss. And part of that was Ray Malavasi, our defensive coordinator. Ray was head coach when we went to the Super Bowl. He taught us a technique that was unbeatable. If you did it right, you were going to win the battle every snap. I believe we went 5-0 to start the season. We looked at each other and said, “This is pretty good. Let’s keep it going.”

That 1973 offseason, is it true that you also had a near death experience.

Merlin Olson and his brother Phil put on a football camp in Utah in the summer. They did it to give back to the kids, but it also gave us the opportunity to go fishing in the afternoon in those mountain streams. Those were really fun times. We had our coaches meeting at a local watering hole. That evening, I was worn out, so me and my wrestling coach walked out of the back of the place, and we saw that two guys had one of our boys pinned up against a car with his girl, and they were harassing them. I walked in between them and said, “You boys just leave them alone and go about your business.” So one of them said, “Well we’ll fight you!” I said, “No not to day, we’re not doing that. Just go on home.” One of them turned and walked away. The other one jawed at me a bit and left.

We were walking back to our truck in the parking lot, which wasn’t lit well. My buddy who was walking ahead of me hollers at me, “Look out, Jack! He’s got a gun!” I had no idea what he was talking about, but I assumed he was talking about one of those boys. When I turned around to see what was going on, I caught the pistol in my right eye. To this day, there’s a time lapse in my memory. I don’t remember what happened. The pain in my eye was excruciating. Blood was everywhere. When I came to, my buddy was holding my arm, I was holding the pistol and I’ve got him on the hood of a car, and my buddy is yelling, “Don’t kill him, Jack! Don’t kill him!” I couldn’t see out of that eye. I turned him loose and went to the emergency room to get sewn up. The sheriff came to the ER and told me, “You know you’re one lucky young man. You caught one of two empty chambers. There were four other bullets in the gun.” All I could think about was that we were about six weeks away from starting training camp, and it’s going to be hard to play with one eye.

Given the physical toll the game takes, how did you play 184 consecutive games?

I was extremely blessed with the physical ability to play. I had some dings and pulls here and there, but no season ending hyperextensions or MCL injuries or anything like that. The other thing was the way Merlin Olsen taught me how to play the game. We loved doing what we did, and we didn’t want anyone to take our place.

You’re being a little modest. You played the entire 1979 playoffs, including the Super Bowl, with a fractured leg!

The moments were difficult, because it was painful. But from the mental perspective, my granddaddy taught me that if you were given a job to do, you want to do it to the best of your ability every time you get the opportunity. It wouldn’t happen today. The coaches wouldn’t trust the player enough with the judgment. If I am burdensome to the team, I’ll take myself out of the game. But I’m the number one defensive end on this team. I’m the captain. This is my team, and this is my job, and I’m going to try everything I can to give us the opportunity to win.

When you left the game as a player, did you have any regrets?

I wouldn’t call them regrets. I would like to have a couple of do-overs (laughs.) I would like to try again against Minnesota. We had three tries on the goal line and couldn’t get in. There are some moments you’d like to have again. We came so close to getting there (The Super Bowl) five times.

When you retired, you were still playing at an elite level. What went into the decision?

I had a blown the S1/L5 disc in my back in a game against Tampa Bay. I’d recovered from that, and I trained harder in 1985 than I’d ever trained before. I was a conditioned freak, because I never wanted my opponent to think they were in better condition than I was. I wanted to have that advantage in the fourth quarter. But I was concerned whether I could play the game in 1985 the way I had for the previous 14 years for a full 16 games. I didn’t want to start a job and then have to quit. I understand that it’s an injury, but it’s still quitting. The owner, Carroll Rosenbloom, told me that I had a position in the front office whenever I was ready. I really wanted to work my way to the top of the front office and help my team. I wanted to find better players, coach ‘em up on the field, put ‘em in a position where they could be successful. My wife chuckles at me, but I tell people, retiring was a tougher decision to make than getting married. You can get married anytime. You don’t always get the opportunity to play in the National Football League. You never lose the desire to play.

What are you putting your energy into today?

My business partner David Allen and I are trying to set up a network across the country for concussion therapy. It’s a neurofeedback treatment that allows the brain to use the energy that it needs to have to heal itself. We’re putting that network together right now. You really need to be careful with the symptoms so you can understand how it’s affecting your behavior.

You were a player at the University of Florida when Gatorade was born. If only you had gotten in on that..

I’m still upset about that! (laughs) They dumped us! All the early guinea pigs! When I was in high school, we didn’t understand the aspects of hydration. If you had water during practice, you were a sissy. “We’re trying to make you tougher!” No, you’re trying to kill me!

At Florida, Dr. Robert Cade (the leader of the Gatorade research) was a mad scientist. He really was. Every day, after practice they would bring a new batch of the witch’s brew that they made up that day. It was nasty at first! One day it was salty. One day it was sweet. One day it was thick and syrupy. One day, you might as well just drink water. And we had no idea what we were drinking. But the coaches and our trainer Brady Greathouse told us, “Well, this is what we’re using for this hydration thing.”

We had a scrimmage one day, and we came over to the sideline. They had started putting it in cans, so the cans were iced down on the sideline in these 10-gallon drums. Mike Kelly, my middle linebacker, bless his heart, he opened that can, knocked it down, and fainted right on the field. The rest of us had the cans in our hand and we said, “Oh crap, we’re not drinking any more of this! (laughs) It wasn’t what was in the Gatorade, it was the cold that got Mike. But I ‘ve thought for years that if they’d just given each of us a half-share, we’d all be financially taken care of for the rest of our lives!