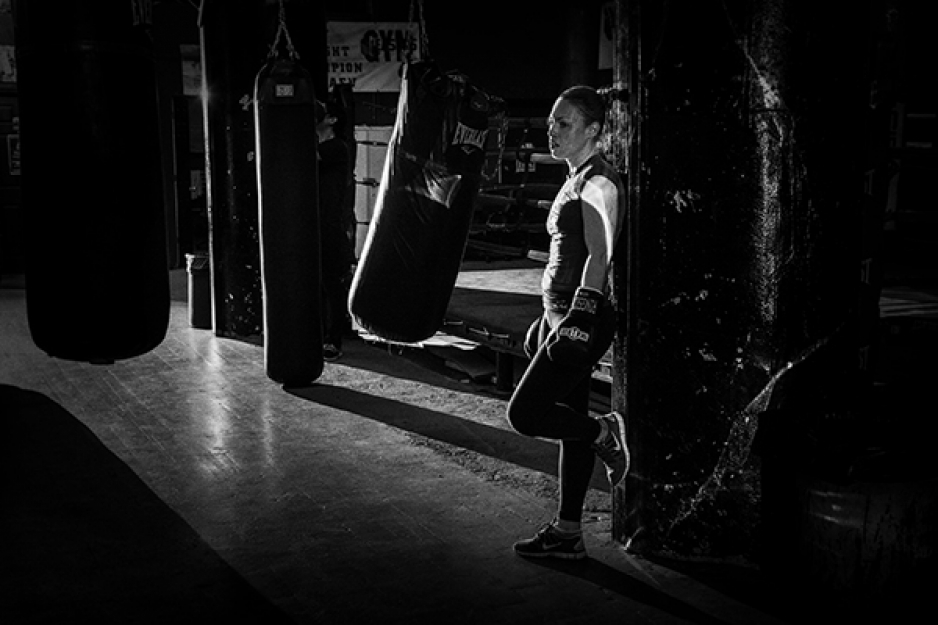

Though boxing is a sweet science, there are many who still believe that a woman need not be tainted by its seductive fragrance. Here At Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn, long known as a laboratory for champions, (LaMotta fought here! Ali! Tyson!), tomorrow’s generation of champions is working in today’s sweatshop, trying to turn incalculable human effort and desire into money. Here, you’ve got to defeat to eat.

On a training table at the back of the gym, a strikingly pretty and fit female boxer with a long blonde ponytail unravels her hand wraps revealing her swollen knuckles, souvenirs from being a professional prizefighter. “Hi, I’m Heather Hardy,” she says, extending the unwrapped hand to greet me. “Pleasure to meet you.”

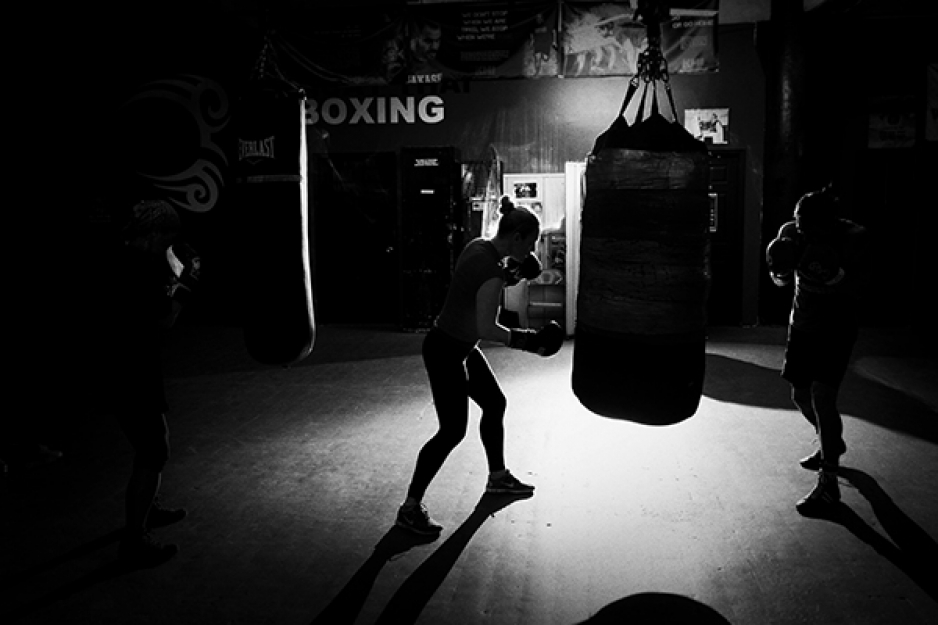

In New York City, Heather “The Heat” Hardy has become the talk of the boxing town. On small fight cards in front of folding-chair crowds, Hardy’s kinetic style—fists flying from bell to bell, turning “The Heat” on her opponent—has attracted a growing audience of males and females alike. And once you get to know Hardy, you realize that her fists-of-endless-fury fighting style is derived from the way life has treated her.

“Please excuse the mess,” she says, as she ushers me into her office at the gym, a small room with a desk, a microwave, a cube refrigerator, and a small lounge chair where Hardy’s nine-year-old daughter, Annie, will sometimes rest before school. “We just put these shelves up yesterday,” she says, pointing to a pair of small wooden wall shelves. “It took us a few hours, but I’m so proud!”

As the sounds of the gym creep through the office door—an electric ring bell, the thumping patter of gloves hitting pads and heavy bags, a not-so-occasional off-color word—Hardy beings to explain how she made the transition from an insolvent single mom from Gerritsen Beach, Brooklyn to an 8-0 professional boxer with her own full-page profile in The New York Times just three days prior.

“I always thought I was going to be the first girl on the Yankees,” Hardy says, laughing. “I always wanted to come running out of the bullpen in the ninth inning. But it wasn’t like I was a bad kid who liked to fight. I was an A student, a real geek. I loved to read literature, poetry. I liked math. I really liked school.”

In addition to being a good student, as the oldest of three children, Hardy also played the role of second mom to a sister and brother, six and five years younger respectively. “My mom and dad both worked two jobs,” she says. “My dad worked on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, and at night, he was a bartender. My mom worked at hospitals all over New York and in Long Island. So since I was in the seventh grade, I would make my brother and sister dinner, get their clothes ready for school and so on. When my sister got her report card, I would be the one that would have to go down to school and talk to the teachers about it.”

Because Gerritsen Beach was a working class area where many residents worked multiple jobs, everyone was seen as extended family of some kind. “I had a million moms and dads running around,” Hardy remembers. “Everybody knew everybody else’s business. I would get the crap beat out of me from my neighbor’s parents if I was ever out of line.”

It was never Hardy’s intention to use that tough training to punch her way out of Gerritsen Beach. Her goal, instead, was to look at the evidence of other people’s fights to determine who was in the wrong.

“I went to John Jay College to study forensic psychology,” she says. “I really wanted to join the FBI. In college, I took the police test, because you needed to have a certain amount of years of law enforcement before you can apply. I was getting ready to do the physical for the cops, and that’s when I found out I was pregnant.”

At age 22, after giving birth to Annie, Hardy went back to finish her final semester and earn her degree. Then she cobbled together a living while caring for her daughter. She worked as a receptionist in a lighting store on the Bowery in New York City. The owner was married at the time to her aunt. “He told me that if I wanted to make a website for him from home, I could do it until I was ready to go back to work. It was really successful. I was good at it. But I still felt like such a big part of my life was missing.”

Hardy was fighting battles on multiple fronts. Her marriage began to fall apart. The FBI dream began to drift away. Immediate bills required immediate employment. She soon found herself in what boxers call “the deep end of the pool.” She was toe-to-toe with the eternal struggle that every working class person faces in their life—what do I want versus what is expected of me.

“After my daughter was born, I felt like a guy in a dress. I was pushing the carriage and going to the park and doing all the other things the other moms did, and I felt like this is not the life I want. I love being a mother. But I grew up in this place where you grow up, you have a kid, you be a mom, and that’s your life. I felt myself being kicked down that path. And I was like, ‘I don’t want to go!’ I want to be a mom, but I still want to have a piece of me left. You’re in a place where everyone is doing the same thing, and you’re like ‘Is it OK that I don’t want to do what everyone else is doing?’ So when I found boxing, it was a real awakening.”

Hardy was walking past a brand new kickboxing gym in her neighborhood and she could hear the bell ring for her. “They offered classes late at night. And my sister was living with me since I had moved out, so she would watch the baby while I would take the classes. And it felt so great to have this little bit of time where I wasn’t somebody’s ex-wife or somebody’s mom. I was just Heather.”

Within three weeks, Hardy was thrust into her first fight. “People wait years before they have their first fight,” she says. “They asked me if I wanted to have a fight before I even sparred! I was like all right. I grew up in Gerritsen Beach. I’ve been getting beat up for years. I’m not worried. My mom always says. ‘No one will ever beat you like your mama.’ So I tried it. And it was the sloppiest, ugliest fight I ever had, but I won. And I did it in front of 2,000 people. My dad cried. My mom was banging on the folding chairs, yelling louder than anyone there. I grew up a really shy person, but for whatever reason, I felt like I was made to do this. It was like a million puzzle pieces came together.”

As Hardy began in advancing in kickboxing, the puzzle became much more complicated. Her divorce became even more contentious. Bills piled up. The refrigerator stayed empty. And her opponents were getting tougher.

“I took some time off from it, because I was going through a really bad divorce,” Hardy says. “I was supporting my sister and both our kids at the time. I went through this transition where I did nothing, but I was so unhappy. I couldn’t keep going on like this. I’m going to leave the neighborhood and make something of myself.”

The last kickboxing fight Hardy had, her opponent handled her convincingly. “I lost to a boxer,” she says, “and I had no idea what she did to me. I had been going home after sparring with grown men, getting concussions and black eyes and bloody noses, and this girl just casually, easily, boxed me for three rounds and walked right through me. I wanted to learn what she did. I went to Gleason’s Gym because in Brooklyn, that’s where people who were serious about boxing went. That’s where I found Devon, and he totally changed my life.”

Devon is Devon Cormack, a three-time world kickboxing champion who once came to Gleason’s Gym himself to become a better boxer. From there, he became a boxing trainer as well. Cormack helped train his sister, Alicia Ashley, who is the reigning women’s WBC World Super Bantamweight Champion.

“When I first saw Heather, she had no skills,” Cormack says laughing at the memory. “I mean nothing. But it was apparent right away that she had a huge heart. You can’t teach that to a fighter.”

Hardy initially worked with Alicia Ashley while she was learning the sport as an amateur, with Cormack serving as a second in the corner. “After I lost my second amateur fight,” Hardy remembers, “ I went into Devon’s office and started crying. At that time, Devon was giving me little advice here and there. I said, ‘I will do anything it takes. I don’t want to lose any more. I will do whatever you say.’ He knew that I had no money. I barely had the money to pay the gym. So he started training me, and he never charged me a dollar.”

Cormack took her on and began to help her transition to the life of a boxer. Hardy would wake up at 4:30 a.m. and take a municipal bus and two trains to get to the gym by 6:00 a.m. to train. Cormack would drive Hardy to schools all over New York City, as she sold student test prep books to make ends meet. Eventually, Cormack taught Hardy how to train members of the gym, so she could work out of the gym. She became proficient enough as a teacher that she could train many of the gym’s female clients, while Cormack worked with his regular clientele. Cormack helped arrange with Gleason’s owner, Bruce Silverglade, to have Hardy work the front desk when there were hours available.

And somewhere between working and being a mom, Hardy had to learn everything she could about boxing. At age 27, she was often over a decade behind her opponents’ schooling. “When you’re an amateur, you have a book that has all your fights stamped in it,” Hardy says. “It’s almost like a passport. My book had one page in it with three fights. Devon starts flipping through my opponent’s book, and it’s pages and pages. I was like, ‘Oh my God, she must have 60 fights in here.’ Devon was like, “Don’t worry. You’re going to be fine.” And I beat her up so bad! I felt so great. I was like, I can do this!”

Within seven months, Hardy had earned a national title as an amateur. It guaranteed her a trip to Colorado Springs to work out at the US Olympic Training Center for three months. Cormack went to work trying to help Hardy cram for a test that her opponents had been studying years to pass.

“Every day, I would cry,” Hardy says. “Devon would have to desensitize me and buy me breakfast. He would say, ‘I don’t hate you. You’re normal. This is all normal.’”

Cormack recalls the intensity of the sessions, “Because of her age, we didn’t have a lot of time,” he says. “She had so much to learn. She didn’t have the skills yet. But she had everything else.”

Hardy went on to win the New York Golden Gloves and turned pro. And that’s when she realized very quickly that the economics of the sport are always going to be far more merciless than any opponent could ever be.

“From the moment I got offered my very first fight, it came with the condition that I had to sell the craziest amount of tickets,” Hardy says. “It was like, alright, if you want your shot, you have to sell $10,000 worth of tickets.” My purse for fighting was only $1,000. Usually you have to sell your purse. I was selling ten times my purse, and I was like, ‘I’ll do it!’ And Devon was like, ‘We’ll do it.’ Cause we know that if I have to stand out with a sign in Times Square or have a fundraiser, I will get that $10,000. If I had to pay for it myself, I was going to do it. It was about 150-200 tickets. But we sold them. That was my hook. The first fight, I kicked ass, everyone was talking about it. So right away, the promoter was like ‘I love this girl!’”

Despite the successful debut, Hardy couldn’t even bring home her entire purse. “My first fight, it was that time of the month,” she says laughing. “The morning of my weigh-in, I weighed in at 126, four ounces overweight. And I knew there was nothing I could do, because you retain water differently at that time. I’m sitting in the sauna, and I feel terrible. The coaches were like, ‘Get her a jump rope.’ And I said, ‘Nope. Barring amputation, it ain’t gonna happen.’ Because I was four ounces over, I had to pay $400 out of my purse to my opponent. My mom was like, ‘Bologna is $4.59 a pound! Those four ounces cost you a fortune!’”

But there are only so many times that you can get your friends and extended family to buy tickets to watch you fight. “I’m from a working-class neighborhood. People can’t afford to watch me fight every month,” Hardy says. “I sell tickets in the gym to people who know me in passing. A lot of times, the people who want to see me most, never get to see me. It’s so stressful. There was maybe one time that I handed back two or three tickets to a promoter, but I don’t want to give a promoter a chance to say, ‘She was such a pain in the ass last time, I don’t want her back on the show.’”

While scrapping her way toward a career as a boxer, life continued to try and keep Heather in the corner. A fire destroyed the apartment she lived in with her daughter in Gerritsen Beach, along with most of their possessions. “It was some faulty wiring from construction that was going on,” Hardy said. “I said to myself, ‘You know what? As long as my kid wasn’t in there, I don’t care.’”

Hardy and her daughter slept on her mom and dad’s couch in Gerritsen Beach until the apartment could be rebuilt. Shortly thereafter, Hurricane Sandy hit.

“It was like a normal rainy day,” she remembers. “It wasn’t like this Wizard of Oz storm. We were waiting for 5:00 p.m. to come, so we could have a few drinks and party a little. Then the water started coming through every crack on the floor. My mother said, ‘Get some towels.’ But by the time we got the towels, it was like, ‘Put everything up on the tables!’ My dad started yelling, ‘Get the kids and lets get out of here.’ We couldn’t get the door open because of the pressure of the water. It was all happening so fast. By the time we tried to leave, the water was up to our knees. My brother helped us get out through the living room window; we got in the car and drove straight up the avenue. Eventually, we had eight feet of water in the house. My family went to the church, and me and my sister took the kids to a friend’s house in Sheepshead Bay.” Hardy’s mom and dad are still living in the church, alongside the priests, until their house is rebuilt.

Through the personal heartache, Hardy kept channeling her energy towards the ring. Her fights continued to win “Fight of the Night” on cards filled with far more decorated male boxers. She continued to hustle and sell as many tickets as necessary, while her opponents didn’t carry the same burden. She signed a multi-year promotional contract with DiBella Entertainment, one of the most prominent boxing promoters in the country, and the first deal of its kind that DiBella has signed with a female boxer.

“Most girl fighters get signed to a few fights, or it’s an unspoken deal that they’ll put you on every other card,” Hardy says. “But Lou DiBella is committed to female boxing. It’s the networks like HBO and Showtime and ESPN that refuse to put females on the cards. Every time I go out, I end up having the “Fight of the Night.” Put us out there, and let people see what we can do, the same way people support Ronda Rousey and Miesha Tate in UFC.”

You can see the fire in Hardy’s eyes as she points to the gym floor at Gleason’s. “There’s a woman out there that holds the same WBC title that Floyd Mayweather has, but she’s lucky if she makes $1,000 a round. People just aren’t exposed to what she’s doing. Every time I go out there, I represent all the girls who fight, because, guaranteed, there will be a handful of boxing fans that watch a female fight for the very first time and make their judgment on what they see. So there’s overwhelming pressure to not just win, but make them remember you. Every one of my fights has to be something people will go home and remember.”

This past September, one of Cormack’s clients helped Hardy find an affordable apartment a few blocks from the gym. It allowed Hardy to enroll her daughter in a public school close to the gym. These days, Hardy and Annie get to the gym at 6 a.m. where Annie will take a nap before school while Hardy trains clients. At 8:30, Hardy takes her daughter to school and returns to train the rest of her clients. Then she trains herself.

At 2:30, Hardy leaves the gym to pick up her daughter from school. “A few weeks ago, my ex came by here to start an argument,” Hardy says pointing to an area across the street. “As he was yelling at me, someone got out of their car to ask me for an autograph. It was one of the greatest moments of my life,” she says.

Hardy picks up Annie and quizzes her about her day and what she would like to have for dinner. They head back up to Hardy’s office in Gleason’s, where Annie is likely the most well protected child in New York City. No Gleason’s boxer will let a stranger near the door of the office where she does her homework, especially, Delen “Blimp” Parsley, a former Golden Gloves finalist and sparring partner for Mike Tyson.

Hardy straps on her headphones and darts out of the gym to run a lap of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, approximately three miles in length. After another hour of conditioning work or skills training in the gym under Blimp’s supervision, Hardy takes Annie home to make dinner and spend some family time together. When Annie is asleep by 9, Hardy will head down to the building’s gym to get one more hour of roadwork in on the treadmill.

“When I’m on that treadmill, it feels like I’m in a hotel,” Hardy says glowing. “When my sister comes to my apartment now, she’s like, ‘Can we order room service?’” Life in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge does have its costs, however. To this day, Hardy’s mom will bring groceries from the much more affordable Gerritsen Beach supermarkets, as the local gourmet shops are far too luxe for the pro boxer lifestyle.

With Hardy’s burgeoning success, sanctioning bodies have inquired about her stepping into the ring for a title shot. Hardy knows the clock is ticking on her career as a boxer. Now 32, she’s at an age where fighters begin winding down their careers rather than amping them up.

“I don’t think I’ll be doing this in 10 years,” she says. “I’d still like to have another baby. But right now, I’m not leaving the sport until there is no doubt, that I am the best. The best!”

For Cormack, the time is not right for the title shot. “In women’s boxing, title shots are not hard to come by,” he says. “The question is, if you get one and win, can you keep it? Are you ready to beat everyone?” Does that include Alicia Ashley, Cormack’s sister and the holder of the most prestigious title in Hardy’s division? “We’ll cross that bridge when we get there,” Cormack says smiling.

“You know,” Hardy says, “When I go out there and see Alicia sparring with Melissa Hernandez, a six-time World Champion, I’ll just stand there and smile. It’s amazing, and the whole world is missing out on it. Boxing fans are missing out on so many epic fights, because they’re women and not men fighting. Every time I go out there, every article I do, we’re one step closer to something.”

On June 14th, Hardy will fulfill another dream. She will be become the first female professional boxer ever to fight at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, an arena just a few blocks from her apartment. Though her fight is on the undercard of HBO’s Boxing After Dark, it will not be televised.

As Hardy sits in her office, she’s delivered two envelopes from strangers. Her first fan mail, courtesy of a profile of her that ran in The New York Times just three days prior. In one letter, a fan sends Hardy a check for $100 to help her with training expenses. As she reads the letter, she begins crying and shows it to Cormack.

“Sometimes, I just sit in here and cry,” she says. “Devon will be like, ‘Why are you crying?’ and it’s because I can’t believe my life went from that to this. My last fight, I headlined the closing of Roseland Ballroom. I come out to the ring and they play Girl on Fire by Alicia Keys. That’s the song I come to the ring to. And the place went crazy! And they’re yelling, ‘Hardy! Hardy!’ and I’m crying. I feel like I’m coming in from the bullpen at Yankee Stadium.”

“That’s what people have a tough time understanding. For me, this is my job. I can paint my nails with you, go in there and beat the crap out of you, and then we can finish painting our nails and have some coffee. It’s not an anger thing. I don’t have this, ‘I hate people and I want to beat them up,’ attitude. This is fun for me! To me, it’s always been fair. You know how many fights in my life have been unfair, where I never had a chance to win? And now you’re telling me, that we both get to wear gloves? And you get to use two hands, and I get two use two hands? And we’re the same weight? This is easy.”

On June 14, Heather Hardy will be the first female pro boxer to fight at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. For tickets, please visit heathertheheathardy.net.